Spring 2017

Inflammatory: (adjective) relating to or causing inflammation of a part of the body; arousing or intending to arouse angry or violent feelings. Provoking. Rabble-rousing.

Pancreatitis is an inflammatory disease. Imagine that inside the pancreas there is a tiny Thanksgiving dinner table that brings together your Democrat and Republican relatives. In a typical year, the conversation might be a little tense and discussions might get a bit heated. But this isolated incident of inflammation is mild and reversible and the family bonds survive. Thanksgiving 2016, however, the political discussion would likely have been much more heated. This dinner likely resembled a severe acute pancreatitis attack in which there is permanent damage to the pancreas along with far-reaching inflammation that leads to multi-organ failure. This can have devastating consequences with a low survival rate despite rapid intensive care.

Pancreatitis in dogs is a poorly understood disease. The Journal of Small Animal Practice devoted its January 2015 issue to pancreatitis in dogs and cats, and the accompanying editorial stated, “The pancreas is a difficult organ to study because of its inaccessibility; no non-invasive diagnostic test is as sensitive and specific as we would wish and biopsy is invasive and has a risk of significant morbidity [causing illness]; the causes of pancreatitis in small animals are often unknown and treatment remains non-specific and supportive…. The problems are more acute in dogs and cats because there is limited research and so little evidence on which to base our decisions on diagnosis and treatment.”

This sounds grim, but fortunately PBGVs are not predisposed to developing pancreatitis. Nevertheless, occasionally PBGVs are stricken with this disease and, for some of those dogs and their families, the outcome can be devastating.

Chance was a fit, active 9-year-old PBGV who had never been sick before. One evening he was in sudden pain and vomiting. The vet ruled out bowel obstruction and gastric dilation/volvulus (bloat). Chance was quickly transferred to a tertiary care hospital affiliated with a veterinary school, where he received a battery of pain meds. They suspected pancreatitis and took a needle biopsy, the results of which were consistent with pancreatitis. Unfortunately, intensive treatment failed to help. Chance developed disseminated intravascular coagulation (that is, blood clotted throughout his body), which led to multi-organ failure. He went from a vibrant dog to euthanasia in 10 days. The clinicians could not find a risk factor that explained his acute disease. His family was left baffled and heartbroken.

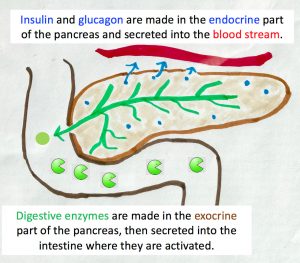

What does the pancreas do? The pancreas is an abdominal gland that helps us convert the food that we eat into fuel for our body. It is divided into two parts. The more well-known part of the pancreas is the endocrine part, which secretes insulin and glucagon into the blood to control blood sugar levels. When the endocrine part of the pancreas fails, the individual will develop diabetes mellitus. This endocrine portion is only a tiny fraction of the pancreas; ninety-eight percent of the pancreatic mass is the exocrine portion. The exocrine part secretes enzymes into the digestive tract to break down the protein, lipid, carbohydrate, and nucleic acid in our food. These enzymes are powerful chewers and they cannot distinguish between the pancreatic tissue that they shouldn’t chew up and the food stuff in the digestive track that they should chew. So, the enzymes are made and secreted in an inactive form and only activated when they reach the gut.

Problems ensue when these powerful enzymes become active within the pancreas itself. If only a small fraction of the enzymes become activated, then control mechanisms kick in and inactivate the enzyme. However, when greater than 10% of the enzymes are inappropriately activated, the control mechanisms are overwhelmed and there is auto-digestion of the pancreatic cells. In response to the damage, immune cells arrive and release molecules called cytokines in an effort to promote healing. If cytokine release is too robust and not controlled, then the pancreas can experience what is called a “cytokine storm”, in which the immune cells cause damage to the tissue rather than repair. (Cytokine storms are thought to be responsible for the deaths that occur in influenza pandemics, sepsis, Ebola and smallpox infections, among other illnesses.) Often the cytokines will inadvertently damage the capillary bed in the pancreas in their misguided effort to help.

At this point, the acute inflammatory storm can resolve if the trigger subsides. If the trigger persists, however, the storm can cause damage to other organs and lead to coagulation of blood within the lungs, kidney and liver. The resultant multi-organ failure is what typically leads to death, rather than the damage to the pancreas itself.

Dryfus was a 16-year-old dog who was treated for pancreatitis his last two years. One morning he didn’t eat his breakfast and was panting heavily as if in pain. A blood test indicated high levels of pancreatic lipase in his blood. He received pain meds, Pepcid and Sulcrate (antacids), and a low-fat food. His panting subsided and appetite returned, but his stool had blood in it periodically over the next few weeks. Over the course of the next two years, Dryfus’s mom kept a diary of his appetite, elimination, treatments, and activity. The diary reads like a roller coaster of celebration when Dryfus ate his meal with gusto, zoomed around the house, or slept through the night, and worry when he wouldn’t eat, was restless and panting, and vomited or had diarrhea. Dryfus’s mom said that she received tremendous support and guidance from a Yahoo Group focused on canine pancreatitis. Through it all, his family tried many different foods and enticements to eat, offering four smaller meals throughout the day rather than one or two larger meals. His meds changed often to try to control his symptoms and make him comfortable. When his quality of life finally slipped, they made the difficult decision to let him go.

What are the signs of pancreatitis? Pancreatitis can be acute or chronic, and mild or severe. Acute pancreatitis generally occurs suddenly and can be mild (with damage that is localized to the pancreas and reversible)

or severe (in which there is death of pancreatic tissue and failure of other organs). Pancreatitis is referred to as chronic when there is mild inflammation that develops slowly. In fact, some dogs may be afflicted with chronic pancreatitis for years without any clinically apparent signs.

Nellie was 5 years old when she had her single attack of acute pancreatitis. Her family noticed that she was stretching a lot as if in discomfort; also, her belly rumbles could be heard from across the room. She was taken to the vet where she received meds for an upset stomach and was sent home. In retrospect, her mom wishes she had insisted on additional tests. Nellie’s condition soon worsened and she developed jaundice. It took two weeks of intensive fluids, antacids, and antibiotics before she recovered. It was much longer before she gained back her full strength. Her family thinks that her episode was due to a prescription food for a urinary tract infection that she was battling. They are now especially careful of the foods and treats that she eats. No table scraps!

Classic signs of Pancreatitis:

- Hunched Back

- Repeated Vomiting

- Pain or Distension of the Abdomen

- Diarrhea

- Loss of Appetite

- Dehydration

- Weakness or Lethargy

- Fever

A dog exhibiting multiple signs should be taken to the vet immediately. From AKC.org

The clinical signs of pancreatitis vary widely. Those with mild disease might only show intermittent loss of appetite and weakness. Chronic low-grade inflammation of the pancreas and subsequent death of pancreatic tissue may lead to other diseases, such as diabetes mellitus or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, with their own sets of clinical signs. The worst cases, those with severe acute disease, might present with sudden onset of appetite loss, weakness, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. These dogs may be in cardiovascular shock and suffering multi-organ failure. These severe acute cases should be referred to tertiary care hospitals for intensive treatment. Unfortunately, the mortality rate for such referred cases in referral hospitals ranges from 27 to 58%.

The clinical signs of pancreatitis vary widely. Those with mild disease might only show intermittent loss of appetite and weakness. Chronic low-grade inflammation of the pancreas and subsequent death of pancreatic tissue may lead to other diseases, such as diabetes mellitus or exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, with their own sets of clinical signs. The worst cases, those with severe acute disease, might present with sudden onset of appetite loss, weakness, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. These dogs may be in cardiovascular shock and suffering multi-organ failure. These severe acute cases should be referred to tertiary care hospitals for intensive treatment. Unfortunately, the mortality rate for such referred cases in referral hospitals ranges from 27 to 58%.

Cooper was 4 years old when he lost his appetite and exhibited acute signs of discomfort and restlessness. Cooper’s mom suspected that he had gotten into some greasy food at the local chowder bar. After several trips to the local vet, Cooper was referred to a tertiary care hospital, where he underwent surgery. Unfortunately, the surgeon offered little hope for Cooper’s recovery and the decision was made to let him go. His mom was devastated to lose her heart dog.

What are the causes of pancreatitis? Dogs of any age, breed, or sex can develop pancreatitis. In most cases, the dogs are middle-aged to senior (> 5 years of age) and the causes are unknown (called idiopathic). Those who are diagnosed with pancreatitis likely have some genetic susceptibility combined with exposure to an environmental risk factor.

Causes of Pancreatitis in Dogs:

- A High-Fat Diet

- Dietary Indiscretion

- Obesity

- Hypothyroidism

- Severe Blunt Trauma

- Diabetes mellitus

- Certain medications

- Genetic Predisposition

From AKC.org

One morning when Desilu was 10 years old, she had a morning appointment with the vet and returned home with a clean bill of health. That afternoon, she began throwing up blood. Desilu was rushed back to the vet and tests indicated that she had pancreatitis. Her mom suspects that she had been eating the rich puppy food meant for the new puppy in the household. Desilu was switched to a low-fat diet and fully recovered. From that time on, her family watched her like a hawk to make sure that she only ate the appropriate food and she never had a relapse.

Among the causes of pancreatitis in dogs are a high-fat diet, dietary indiscretion (which is vet-speak for a dog that has eaten an entire package of hot dogs or some other no-no), and obesity. With a PBGV in the house, we have all learned the hard way to push scrumptious food to the back of the kitchen counter and to keep a sharp eye on our hound who can sniff out tasty trash during walks through the neighborhood. I know from personal experience that a moment of inattention in the kitchen can lead to the disappearance of a ham steak, a chunk of deer sausage, or a wedge of brie. In a dog with no other risk factors for pancreatitis, perhaps that indiscretion will simply lead to a single bout of vomiting or diarrhea. In combination with other risk factors, a susceptible dog might get very sick.

One PBGV was diagnosed when she was 10 years old. Her family brought her to the vet when she vomited, was arching her back in pain, and had black stool. Blood tests revealed high pancreatic lipase levels, indicative of pancreatitis. Her family thinks that, in retrospect, this picky eater had very mild chronic pancreatitis for several years. The acute attack was likely triggered by a home cooked pork meal that had too much fat. She went on Pepcid for her stomach, Tramadol for pain, and the antibiotic Flagel. From then on, her family kept her on a strict, home-cooked low fat diet, which fully managed her symptoms.

On the other end of the appetite spectrum was Star. No one could ever call Star a picky eater. She ate everything she could get into her mouth, including a leather jacket, slipcovers, underwear, stuffed animals, and a pound of chocolate chips. She and her littermate, Preacher, were both on Comfortis (to kill fleas). Preacher was 4 years old when he had his first symptoms of pancreatitis; Star had her first symptoms at 5 years old. Their mom is convinced that the Comfortis was a trigger since the symptoms stopped and started when she stopped and started the flea treatment. Despite eliminating this trigger, Star’s dietary indiscretions ultimately led to abdominal bleeding and severe acute pancreatitis symptoms. Fortunately, Preacher is doing well at age 13.

In humans, the majority of individuals with recurrent pancreatitis have genetic variations in genes that control pancreatic enzyme activation, coupled with environmental stressors such as alcohol or tobacco use. In dogs, it is likely that genetic factors also play a role since certain breeds are predisposed to the disease.

While alcohol and smoking are probably not contributing factors for the typical PBGV, there are drugs that have been associated with pancreatitis in dogs. These include azathioprine (used for immune-mediated disorders), potassium bromide with phenobarbitone (used for seizures), organophosphates (an insecticide), asparaginase (a chemotherapeutic agent used for lymphoma), sulphonamides (an antibiotic), zinc (an essential trace element that is toxic at high doses), and clomipramine (used to treat behavioral disorders). The interaction of specific drugs with genetic susceptibilities to pancreatitis has not been proven or disproven; to do so would require studying large numbers of dogs of various breeds.

The Amazing Al needs very little introduction. Al was a TDI-registered therapy dog who entertained children, seniors, and PBGV enthusiasts with his tricks and performance routines. Unfortunately, Al always had a sensitive tummy. Periodically he would pace in the night and then throw up. When he was 13, he had an acute episode and tests revealed that he had pancreatitis. Al was already on Dr. Jean Dodds’ liver cleansing diet of equal parts of sweet potato, potato and white fish. He also got baked chicken, eggs, white rice, and cottage cheese. After the pancreatitis diagnosis, Dr. Dodds recommended continuing the liver cleansing diet. He did best when his mom fed him 10 tiny meals every day. The only treats he was allowed were chicken and Rice Chex. He could no longer tolerate even the lowest fat kibble after the acute attack. Al had these periodic pacing and vomiting episodes from the time of his pancreatitis attack until his death. Of course, they were usually at night. His family had medications on hand to help him through, including Carafate to coat his stomach, Reglan for nausea, Pepcid to settle his stomach, and Tramadol for pain. Al’s career of entertaining came to an end when he was 14 and a half. His mom said “The pancreatitis didn’t get Al; he just wore out.”

The Amazing Al needs very little introduction. Al was a TDI-registered therapy dog who entertained children, seniors, and PBGV enthusiasts with his tricks and performance routines. Unfortunately, Al always had a sensitive tummy. Periodically he would pace in the night and then throw up. When he was 13, he had an acute episode and tests revealed that he had pancreatitis. Al was already on Dr. Jean Dodds’ liver cleansing diet of equal parts of sweet potato, potato and white fish. He also got baked chicken, eggs, white rice, and cottage cheese. After the pancreatitis diagnosis, Dr. Dodds recommended continuing the liver cleansing diet. He did best when his mom fed him 10 tiny meals every day. The only treats he was allowed were chicken and Rice Chex. He could no longer tolerate even the lowest fat kibble after the acute attack. Al had these periodic pacing and vomiting episodes from the time of his pancreatitis attack until his death. Of course, they were usually at night. His family had medications on hand to help him through, including Carafate to coat his stomach, Reglan for nausea, Pepcid to settle his stomach, and Tramadol for pain. Al’s career of entertaining came to an end when he was 14 and a half. His mom said “The pancreatitis didn’t get Al; he just wore out.”

How is pancreatitis diagnosed? Diagnosis of pancreatitis is a challenge since the disease is characterized by non-specific findings. Suspicion of pancreatitis should be raised if a dog has clinical signs plus a potential risk factor, as described above.

Dogs suspected of having pancreatitis should undergo a complete blood count, serum biochemistry profile, and urinalysis. These tests may exclude other diseases that are suspected. Abdominal radiographs are also typically taken to exclude other diseases.

The most sensitive test of choice, called Spec cPL, measures a pancreas-specific lipase in the dog’s serum. Transabdominal ultrasound is the imaging method of choice for diagnosis of pancreatitis but its accuracy depends upon the ultrasonographer’s expertise. There are also more advanced diagnostic imaging techniques that are used in humans; however, these are typically not available for small animals and are also very expensive.

The gold standard of diagnosis is histopathology; however, that requires anesthetizing the dog for a biopsy and is too invasive (and expensive) in most cases. Histologists will look for the presence of inflammatory cells, fibrosis and death or loss of exocrine tissue. Even histopathology is not perfect, however, since inflammation might be localized to one region of the pancreas and the biopsy might be taken from another region that is normal. Alternatively, pancreatic lesions might be seen that are clinically insignificant.

Patch was 4 years old when he started vomiting and showed signs of being in pain. Ultrasound and a pancreatic lipase test confirmed a diagnosis of pancreatitis. At the time, he was overweight and had been put on grain-free food. Patch received antacids and was switched to a low-fat food. Fortunately, he has not had another bout of pancreatitis in the past 6 years. Patch has developed pulmonary fibrosis, however, which is suspected to be a secondary injury caused by the acute pancreatitis.

How is pancreatitis treated? In human medicine, an individual with signs of pancreatitis will be assessed with clinical, pathological, and imaging tests. Their severity of disease will be scored in a standardized manner. Humans with acute pancreatitis receive standardized treatment that includes early aggressive fluid therapy, analgesia (pain relief), and early feeding. There is general agreement among clinicians that this standardized diagnosis and treatment has led to reduction in mortality from pancreatitis.

Unfortunately, veterinary medicine does not have a standardized method for scoring the severity of canine pancreatic disease. Also, there is not a similar consensus on treatment of pancreatitis in dogs. Current treatments are mostly based on case studies, laboratory research, expert opinion, and extrapolation from results in humans. Thus, it is difficult to predict the severity of the disease or the dog’s prognosis. Nevertheless, there have been efforts to standardize treatment for dogs with acute pancreatitis. This has resulted in the following current recommendations:

- Severe acute pancreatitis should be treated in a referral veterinary hospital’s intensive care unit due to the high level of nursing support needed.

- Intravenous fluid therapy is typically needed to counter the dehydration resulting from vomiting and lack of eating. Either saline or lactated Ringer’s solution are commonly given. The possible benefit of lactated Ringer’s solution is that it is an alkalinizing fluid (that is, it increases pH) and may prevent further inappropriate activation of pancreatic enzymes within the pancreas. There has been no proven benefit of transfusing plasma into dogs with acute pancreatitis, unless the dog is exhibiting coagulation problems.

- Antiemetics are recommended for all dogs with acute pancreatitis. Clinical signs of nausea include licking of lips, swallowing attempts, and obvious aversion to food. Antiemetics should be given even to those with no overt signs of nausea or vomiting because this may encourage voluntary eating.

- Pain should be managed. It is safe to assume that all dogs with acute pancreatitis are in pain to some degree. In order to manage the pain with the appropriate analgesics, it is important to determine the level of pain that the dog is experiencing. A dog with mild pain might be responsive to his/her surroundings, but be unsettled. With moderate pain, a dog might be reluctant to move and may flinch when his/her abdomen is palpated. A dog in severe pain may be non-responsive to surroundings and may scream or snap when palpated. Most referral veterinary hospitals have pain management specialists who can assess the level of pain a dog is experiencing and prescribe the appropriate combination of analgesic agents.

- Food and water should be offered early in the recovery phase. The role of nutrition in treatment of acute pancreatitis has changed over the past two decades. It was previously thought that pancreatitis patients (both human and animal) should fast in order to ‘rest’ their pancreas. Current recommendation is that dogs with mild acute pancreatitis be allowed to eat voluntarily. If the dog does not eat for five days, then a nasogastric tube should be inserted for enteral feeding of a liquid diet. Dogs with severe acute pancreatitis should receive interventional food as soon as possible. Generally, during recovery from a bout of pancreatitis, a low-fat diet is given for a period of time after which a regular diet can be reintroduced (unless the dog has high serum triglyceride levels). Once a dog has had pancreatitis, the chances of a recurrent event is high. The dog’s diet must be monitored vigilantly and his/her treats selected with care.

Dottie was 11 years old when she became agitated, started pacing around the room, and began to bite the wooden knobs on a dresser. She then stretched her body out with her rear in the air. She was taken to the vet immediately. Blood tests indicated an acute bout of pancreatitis. Ranididine (Zantac) was given to reduce stomach acid production and she recovered over the course of a week. The cause of her attack was never known, but her family kept her on a low-fat diet as a precaution. Whenever her mom thought she might be have another attack, she was given the Ranididine and it never recurred. She is 14 now and a hearty eater who loves her walks and a cuddle.

Lessons from the hounds. What can we learn about pancreatitis from our beloved hounds? Several members of our collective pack suffered bouts of pancreatitis after a high-fat feast, either a cup of chowder or some puppy food or a delicious home cooked meal with too much fat. For others, there was no known dietary indiscretion, but it is reasonable to assume that fat was a contributing trigger since switching the dogs to a low-fat food and closely monitoring all foods and treats prevented recurrence. Many affected dogs can have good quality of life if their pancreatitis is caught early and treated with special diets and/ or medications for the rest of their lives. For other dogs, the inflammatory storm rapidly spread to other organs and the most advanced veterinary care was in vain. We hope that research into the causes of pancreatitis in dogs and development of specific treatments will, in the future, increase survival of those suffering severe acute attacks.

Abraham is our elder statesman at 17 years old. His first bout of pancreatitis occurred when he was 11. His mom noticed that he seemed uncomfortable walking and wouldn’t lay on his tummy, which was his usually resting position. The emergency vet gave him pain meds and performed tests that revealed signs of pancreatitis. The vet put him on a bland, unappetizing canned dog food, which Abraham totally rejected. His mom experimented with a modified Dodds’ liver-cleaning diet and Abraham’s appetite picked up. To this day, he cannot tolerate any fat in his diet. He gets three meals a day of a super low fat kibble mixed with white fish, dry curd cottage cheese, and baked sweet potato. Sometimes he gets boiled chicken instead of fish, canned pumpkin instead of sweet potato, and some jasmine rice. Sounds yummy to me! Abraham’s family surmises that his attack was triggered by his habits of rooting through the kitchen garbage and eating poop. They are vigilant on both accounts and, with his diet controlled, his chronic condition has been managed. Abraham has had a very active life, with Rally Advanced and Utility Dog titles. It is wonderful that he can rest easy in his senior years, knowing that most of the delicious cooking in the household is for him.

References:

AKC.org health article. December 17, 2015. Pancreatitis in dogs – symptoms, causes, and treatment. (http://akc.org/content/health/articles/pancreatitis-in-dogs/?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_ campaign=yourakc-20161226); LaRusch J. and Whitcomb, D.C. 2011. Genetics of pancreatitis. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology 27: 467-474; Mansfield C. and Beths T. 2015. Management of acute pancreatitis in dogs: a critical appraisal with focus on feeding and analgesia. Journal of Small Animal Practice 56: 27-39.; Watson, P. 2015. Canine and feline pancreatitis: a challenging and enigmatic disease. Journal of Small Animal Practice 56: 1-2.; Watson, P. 2015. Pancreatitis in dogs and cats: definitions and pathophysiology. Journal of Small Animal Practice 56: 3-12.; Xenoulis, P.G. 2015. Diagnosis of pancreatitis in dogs and cats. Journal of Small Animal Practice 56: 13-26.

Leave A Comment